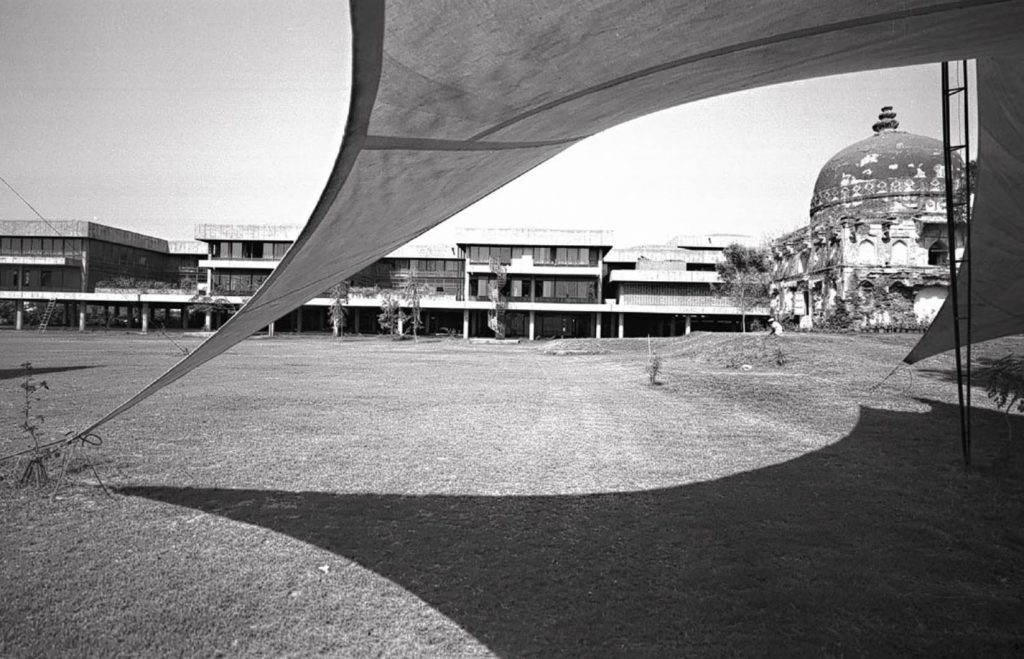

One day, after concluding my years at a girls’ school in Calcutta, somehow scraping safely and relatively unscarred through the West Bengal Board education system, I walked down a red-brick-and-concrete corridor which opened onto a lawn on one side and aquarium-like rooms on the other. The floors above were supported along the lawn by fat cylindrical pillars that were painted red, yellow, blue and green—an experiment with primary and secondary colours, I was told when I asked.

I was walking down the corridor of the National Institute of Design, widely known as NID, in Ahmedabad. In the aquariums, as the rooms were called, surprisingly transparent interviews were being held to select forty students for the new academic year. I had been selected as an interviewee on the basis of a sort of self-assessment and a visualisation test. There would be no further tests: only a workshop to play with materials, and an interview. When I walked out of my interview onto the lawn beyond the pillars, my heart was in a flutter— school had not prepared me for the extraordinary possibility that I could receive an education without being buried under dry textbooks. That I could, instead, learn and understand the nature of things by drawing—the geometric structure of the gulmohar flowers that were strewn around the lawn, the perfect sans serif O, or my own Bangla typeface. I could learn to use a lathe to turn wood or clamp-dye cloth for my clothes, or watch French New Wave films alongside Indian avant-garde ones. I quickly lost my heart to this place on the bank of the Sabarmati river.

Sourav Sil | NID

The overwhelming gulf that I had recognised that day, between a regular school education and a radical design one, led me to look back at my life forever as ‘before NID’ and ‘after NID’. ‘Unlearning’ was a key feature of the discourse in the Foundation Programme for new entrants who were encouraged to question and critique social conditioning. I became part of the NID experiment: a pedagogical investigation similar in spirit to two others that had originated a hundred years ago.

Sourav Sil | NID

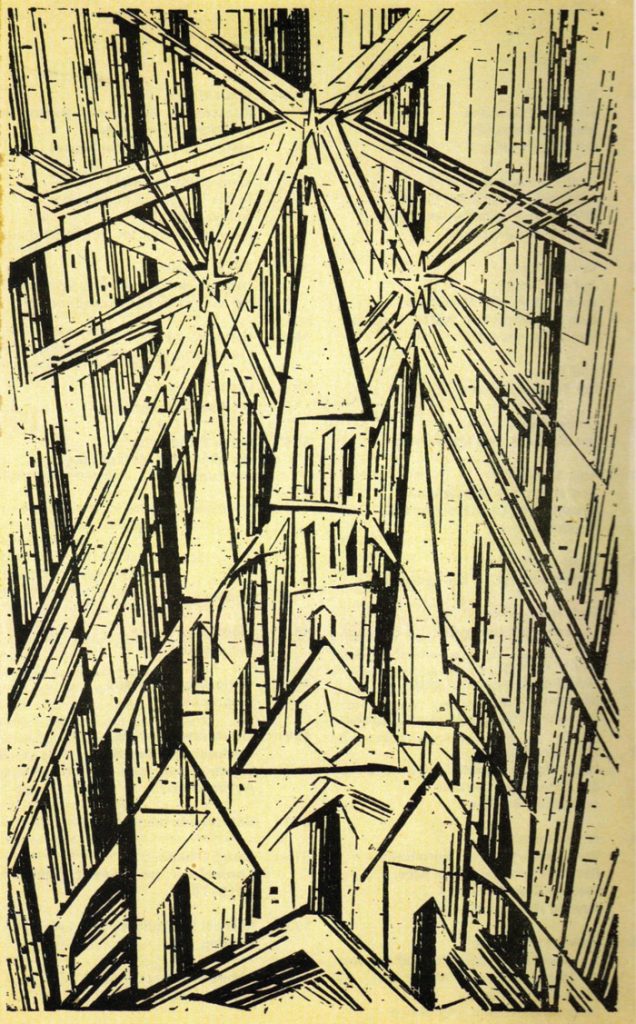

In 1919 Walter Gropius published the Bauhaus Manifesto and Program and established the historic school in Weimar, Germany. The Bauhaus sought to remove distinctions between the fine arts and the decorative by bringing together architect, artisan and artist. Established after World War I during a period of relative political stability, a growing economy and a cultural renaissance, the school was founded on the optimism of a new democracy in the process of imagining its future. The Bauhaus existed in three cities at different points, in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin, under several directors, before it closed down in 1933 under pressure from the Nazis. Despite its short life, it had a profound impact on design, art and architecture around the world, and its ideas continued to spread to other countries with its emigrating members.

Also in 1919, in India, Rabindranath Tagore founded Kala Bhavan in a rural campus in Santiniketan, a few hours from Calcutta. The campus embodied his anticolonial Modernism: free-spirited creativity, ecocentrism and a master-apprenticeship collaboration. Tagore did away with conventional classrooms; lessons were frequently held under the shade of trees around the campus of the university which he set up after Kala Bhavan. Metaphorically, too, he left the doors wide open for influences of ‘universal learning’ as the name Visva-Bharati implied. The curriculum at Kala Bhavan drew from India’s craft traditions and pan-Asian sources as well as Western influences like the European avant-garde and the British Arts and Crafts Movement. The artist Nandalal Bose, who studied under Abanindranath Tagore, the founder of the Bengal school of art and Rabindranath’s nephew, was the first principal of Kala Bhavan.

Source

In 1922, Stella Kramrisch, a Viennese art historian who was also a teacher at Visva-Bharati, curated an exhibition that brought the Bauhaus to Calcutta. Works by Paul Klee, Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky and other Bauhaus artists were presented alongside those of Indian modernists like Nandalal Bose, Sunayani Devi, Abanindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore, who were developing India’s own Modernism through the folk idiom. Many of these Bengali artists were affiliated with Santiniketan.

NID’s founding chairman, Gautam Sarabhai, outlined the school’s educational philosophy, emphasising the unconventional Bauhaus approach of learning-by-doing.

A few decades later, in 1961, not unlike the Bauhaus, NID, too, was conceived as part of an institution-building process in a young democracy. Independent India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, invited American designers Charles and Ray Eames to propose a way forward for the development and modernisation of a largely rural nation using design as a social engine. The Eameses travelled around the country and produced The India Report in 1958, in which they wrote of the humble lota (a metal vessel for carrying water) as a metaphor for the perfectly designed quotidian object that is rooted in local culture.

In their report they engaged with ideas such as what modernisation might mean in a country with ancient traditions and how to train socially responsible designers who would see design as a value system. They recommended “a restudy of the problems of environment and shelter… to restate solutions to these problems in theory and in actual prototype; to explore the evolving symbols of India.” Of NID’s students, they wrote, “We would hope that those leaving the institute would leave with a start towards a real education. They should be trained not only to solve problems—but what is more important, they should be trained to help others solve their own problems. One of the most valuable functions of a good industrial designer today is to ask the right questions of those concerned so they become freshly involved and seek a solution themselves.”

To these already well-established courses, new teaching methods like crafts documentation and environmental perception were added at NID to raise awareness among students of design of socio-economic conditions in different parts of the country as well as to exchange and document knowledge, and create a fertile ground for local culture and skills.

NID’s founding chairman, Gautam Sarabhai, outlined the school’s educational philosophy, emphasising the unconventional Bauhaus approach of learning-by-doing. Platforms like consultative forums where faculty and students could discuss their educational goals together, and the jury system in which work could be evaluated qualitatively, were introduced. The curriculum was experimental and flexible, and it was constantly refined as the institution evolved. Designers, architects and cultural practitioners like Adrian Frutiger, John Cage, Frei Otto, George Nakashima, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Louis Kahn and others were invited to visit and work at NID through its formative years, while young faculty from NID were sent to schools abroad for exposure to various curricula.

The Foundation Programme—the first year—at NID drew from the pedagogies of both the Bauhaus and another well-known German design school, the Hochschule für Gestaltung (Hfg), Ulm, a successor to the Bauhaus and founded in 1953. Just as the Bauhaus and Viswa-Bharati shared synchronicity, Hfg Ulm and NID were founded to advance modernisation in a post-World War II and a post-Independence nation, respectively, and to help with the transformation of society through design education. NID’s first teacher, Kumar Vyas, designed the Foundation Programme in collaboration with Hans Gugelot of Hfg Ulm. The pedagogy of the ‘preliminary’ year or the Bauhaus Vorkurs included exercises in understanding basic elements of design like form, colour and materials in tandem with workshop experiences and theory classes. To these already well-established courses, new teaching methods like crafts documentation and environmental perception were added at NID to raise awareness among students of design of socio-economic conditions in different parts of the country as well as to exchange and document knowledge, and create a fertile ground for local culture and skills.

As we floated around the campus, part students, part autodidacts, we absorbed a very particular way of life: slowness, the love of materials and making things and, importantly, a socialist outlook towards life.

I spent five years at NID where, from the beginning, the very architecture of the place welcomed me as if into a warm home. Designed by the brother-sister duo Gautam and Gira Sarabhai, the NID building was almost a non-building. There was no imposing entrance or façade. Upon entering its main gate, one mostly saw trees and pathways and patches of perfectly built red-brick. I can barely recall walls—studios and classrooms were mostly made of giant sliding rosewood windows, which opened out on to the lawns, trees and the plaintive call of peacocks. It was a vast horizontal spread, but not a maze. It was a grid—so you could always find your way around it intuitively. The scale of things, the materials used and the aesthetic were humanist. There were classic pieces of furniture to sit on, an old monument which was the backdrop for all ceremonies on the lawns and many other instances of such seamlessness between the old and the new, the hand-made and the machine-manufactured. As we floated around the campus, part students, part autodidacts, we absorbed a very particular way of life: slowness, the love of materials and making things and, importantly, a socialist outlook towards life.

Twelve years into my design practice in which I mostly worked with print design, I felt it was time to return to my alma mater and transfer the knowledge and experience I had collected to newer generations. The opportunity arose and I was invited to teach at NID. Much in the way we were taught with no final end product in mind, I started designing my courses as well as suggesting new courses to the department to expand the curriculum. The department I taught in was encouragingly open and, as in the past, things could be discussed and reimagined. As I went along with my modules, I fine-tuned my teaching methods and encouraged critiquing, questioning and classroom reviews. It seemed to me to be the most meaningful way to give back to a place that had given so much; and it was, of course, a homecoming.

Marcel Breuer’s furniture lay around, reminding me of the way Nakashima’s chairs were strewn around NID. It made me acutely aware of the rich history into the tapestry of which my life had been interwoven.

Last month I took a train from Berlin to Dessau and visited the Bauhaus in its centenary year. As I entered and was removing my coat my German friend handed me a card that was lying in the locker room. It had a photograph of the tall tree that stood across from the workshops at NID, which we used to walk past every day on our way to our studios. And so I walked into the Dessau building with an odd sense of the familiar: I stood in the classroom where Josef Albers taught and the office Walter Gropius occupied. Marcel Breuer’s furniture lay around, reminding me of the way Nakashima’s chairs were strewn around NID. It made me acutely aware of the rich history into the tapestry of which my life had been interwoven.

Image: author

Image: author

A large exhibition on the Bauhaus was on display at the new museum building in Dessau. Documentation of the pedagogy developed there by the various masters, Kandinsky, Klee, Itten, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and others, reiterated the transcultural and continental links between the schools. One of the wall texts at the exhibition read, “In his book From Material to Architecture (1929) Laszlo Moholy-Nagy wrote a chapter on educational matters. Therein, he summarized the pedagogic credo of his Bauhaus colleagues wishing to overcome the ‘segmented human’… Consequently, the teaching at the Bauhaus was meant to be radically fundamental, exempt from the established canon. The focal point was not only the vocational qualification but also the acquisition of creative ability on the basis of extensive craftsmanship….” These words summarise the legacy of the Bauhaus which called for a paradigm shift in education that schools, even today, would do well to heed: to treat learners as potentially creative individuals, abandon mere reproduction of knowledge and encourage knowledge gained through independent observation, critical consideration and training of all the senses.

**

Rukminee Guha Thakurta is a graphic designer who has designed books for museums, publishers and artists around the world. She teaches design at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, of which she is an alumnus, and at other institutions in India and abroad. Music and yoga are serious hobbies for her.

First published in the Indian Quarterly magazine under the same heading.