The transitory quality of the Indian city remains its most permanent and visible attribute. In the 25 years that I have lived in Delhi, I have only known its incompleteness and incoherence. At one time perhaps, there was a city structure assembled on the ground. It was based on a germinated plan, and the belief that people had come to live together for a reason. Whatever that reason, their presence required a framework, a geometric cohesion that set a comprehensive structure to their city and to their lives. Something that influenced their work, their play, their very movement, their life and time in the city. But the history of that cohesion has now sunk below the surface, and there remains only a lingering sense of its once-complete picture—a broken tomb here, a collapsed madrasa there… Now, a glass building is rising, a masonry one is decaying, another is being pulled down. A house is acquiring a second floor, a barsati is being renovated. Telephone lines are being dug, new Internet cables put in. Every public act is an acceptance of the growing numbers of people. The city resident will possess all that is within grasp, altering the public environment to suit his private purpose. The Indian city is like a motion picture in perpetual slow fade, a film with no end.

Some years ago, I attempted to capture something of this perennially changing cityscape by photographing one building, from one spot, at monthly intervals for a period of three years. I figured that that transitory urban state would reveal itself best in the steady and structured sequences of time-lapse still photography—36 frames that would record the birth, growth, decline, death and rebirth of a single piece of the cityscape. The building was a set of government flats near my own house. I found the same spot on the sidewalk on the first day of every month, and directed the camera to precisely the same angle for the photograph. When viewed as a sequence after three years, the building rose out of the ground, its brickness was plastered, painted, people moved in, flower pots appeared on the balconies, blouses and underwear dried on terraces, cracks appeared on the walls, rain stained them black, peepal began to grow in crevices…

I knew nothing of the people behind the façade, but the act of occupying a structure with a continually changing public face gave me a brief insight to collective living. I saw the changes that came over individual balconies; the compositional alteration that affected the whole façade; and I saw the changing environment of people’s lives in frames that revealed everything when viewed as a shuffling rush of playing cards.

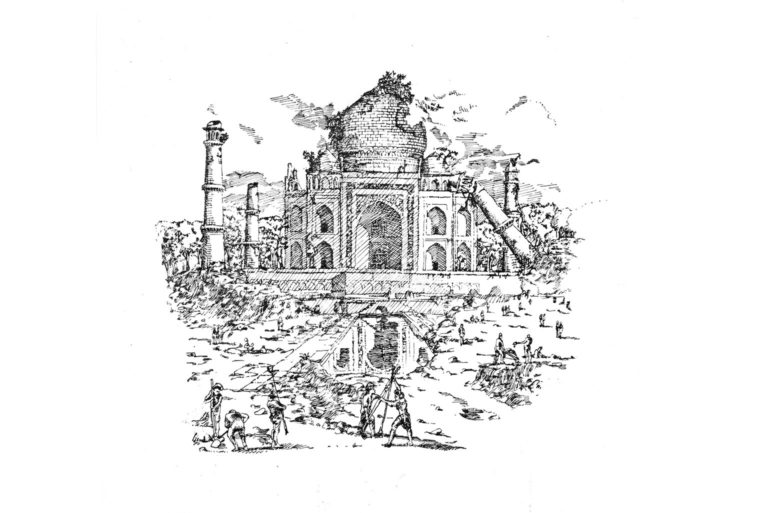

For an architect, photographing architecture is a sort of memoir. Drawing, however, is an even more intimate medium to comprehend the transitions and conflicts between the building and its place in the city. For me personally, drawing is an attempt to document the transitory nature of architecture itself—not just its immediate intentions and goals, but also how it will engage with the weather and people, how it will age and decay, and the conditions that will bring about its eventual collapse. Drawing allows an exaggerated view of that impending reality. Parts of my drawn city are destroyed by time, others by man-made and architectural catastrophe. The destruction of familiar landmarks, or those that are altered for commercial reasons—the ruins of Connaught Place, the fragment of a newspaper, India Gate as a hotel—create the memory that we may experience in some not-so-remote future.

Gautam Bhatia is a Delhi-based sculptor and architect. Besides a biography on Laurie Baker, he is the author of Punjabi Baroque and Other Memories of Architecture, Silent Spaces and Malaria Dreams and Other Visions of Architecture. He is currently working on “Future Building”, an exhibition of ideas for the future city.

This article was first published in the indianquarterly.com