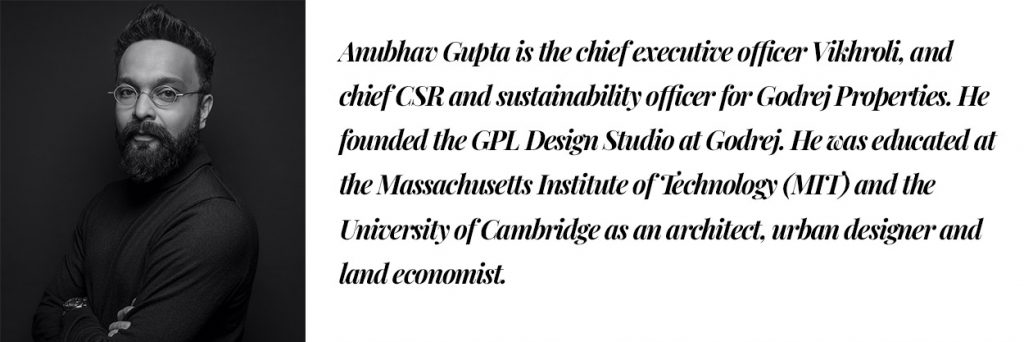

For the 10th episode of the Those Who Design series, I am pleased to have Samira Rathod with me at The Trees in Vikhroli. With over 25 years of design practice based in Mumbai, Samira has projects spread across the country with many awards to her credit. She is critically interested in theory of architecture and has published many editions of her own magazine called Spade. On this beautiful summer afternoon, I look forward to discussing her recently completed project — The School at Bhadran in Gujarat, India to understand her inspirations, aspirations, approach and learnings.

Project origin

From the outset of our conversation, I am struck with Samira’s honest, ‘what you see is what you get’ demeanour. She jumps right into the project giving me an overview of the small town of Bhadran which is known as the Paris of Gujarat owing to its fairly sophisticated development quotient with well laid out drainage, exquisite houses, temples and other civic amenities. The school project of the new English medium school was meant to be an extension of an existing facility on a land with a lush chikoo orchard. Samira’s design response was to build on stilts which meandered around the trees in such a way so as to give the school children the ability to pluck chikoos from the verandah. Unfortunately, she shares that the site was not to be due to lack of development permissions on the land. Hence the site moved to a rural location without any trees. In choosing to respond to the lack of context in a different way, unapologetically, Samira decided why not plonk the same plan to test this notion of transference on the rural site where new trees would need to be grown in any case. While I may not have responded in the same way, I found her self-awareness for not having any qualms and openly sharing this approach quite honest and believable as an alternative way of doing it.

The big moves

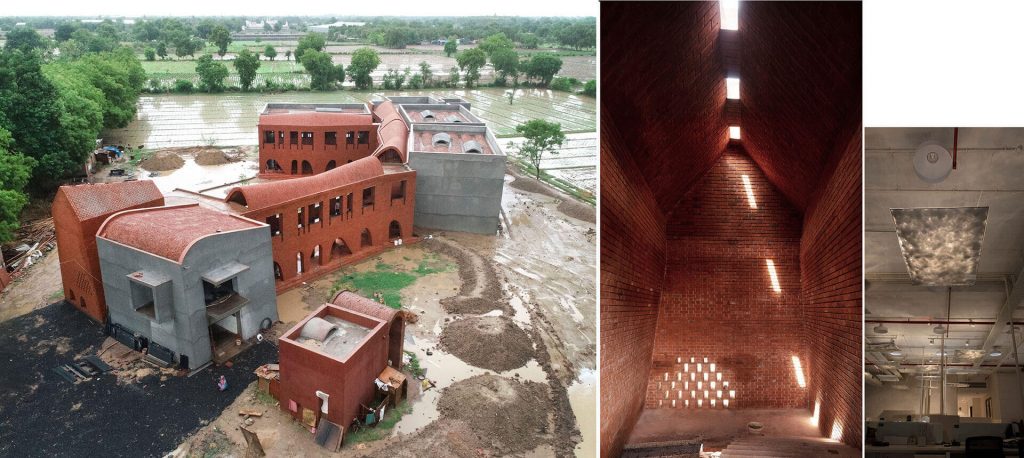

With perhaps the biggest move already made between the sites, I asked Samira for other moves that had inspired the design we see today. Going back to the available context of Bhadran, she invokes the beautifully crafted old homes with their arches, the prevailing landscape as one drives from Baroda to the town, and, the brick kilns that lined the journey which got her design impulses moving. In asking herself – what the building will look like, she intuitively began to investigate on how children write. When you give a child a pencil, one typically finds playful scribbles which almost dance on paper. In her words, this was it. This was how the arch of The School at Bhadran which became lopsided as a scribble put together with other such arches began to dance in brick as the school of dancing arches.

Form, Function and Materiality

Samira shares that the building is conceived as a module of which they built phase 3 after which phases 2 and 1 were to follow. This was the senior school of about 20,000 sq ft. consisting of classrooms, labs, administrative area and a library. The rest of the classrooms and the school would be built later. She states that her intervention as an architect was decisive at this point. Since this was a semi-rural area, she wanted to design in a way such that the administrators could make the additions on their own without necessarily reaching out to the architects. This meant designing a module and system framework where forms could be repeated in permutation and combination to get the desired function, enough differentiation, yet standardisation of building with ease with repeatable building techniques and construction technology. Samira articulately breaks down the building into its components of the blocks, skin and roof which are able to twist and turn whilst being added on to a spine bringing about this notion of a dance in the way the building is put together. She refers to how two roof vaults can be put together in different ways to get patterns and how a connector piece enables expansion akin to a Lego block. She adds that the jack arched vaulted roofs of the blocks use the same shuttering in different directions to form Type A and Type B classrooms. Going from an intuitive response into a workable system framework that does offers both differentiation as well as standardisation whilst enabling ease of expansion makes for a commendable effort.

These efforts clearly saw a fair share of challenges. Amongst these Samira candidly shares resistance from contractors on the use of exposed brick and its implications on cost. Her belief that one need not go to most expensive agency, rather invest in robust supervision and show how it’s done to yield great results. Luckily, she says the brick tested well and she was comfortable with a handcrafted look and blemishes if any over a machine made aesthetic. Samira elaborates on the challenges of laying out a series of lopped dancing arches with respect to calculating load transfers and where the keystones may sit, all to provide support to yet another lopsided vault which danced on top if the skin. Clearly a test of any structural consultant and a contractor worth their salt. At this point Samira’s journey throws out another curved ball. With much resistance, negativity, serious negligence and cost overruns she confides that she had to let go of her entire construction team and together with support from her generous client embarked upon hiring a new one. It finally paved the way for a positive, more supportive contractor who she gives due credit for the roof, over her engineers. She explains that the thin concrete vault is supported by brick which is laid without mortar – a cost effective solution which was far better than a clunky concrete slab initially recommended by her engineers.

The Enquiry

My first line of enquiry was to understand the use of vaults as it does limit roof usability in comparison to a flat roof, assuming it was for climate comfort. Samira confirms that it did serve that purpose including for the provision of cross ventilation. In referring to the vaults over the classroom blocks, she mentions a few decisions made on site once they were comfortable in the use or construction of certain materials. Anticipating my next question, Samira brings up the challenges of waterproofing on top of undulating vaults which she consciously chose not to fill. While the typical response would have been to figure out a viable waterproofing strategy, Samira’s approach was more basic – simply to drain the water where needed. This idea resulted in yet another imageable characteristic of the building – a dance of water spouts generously placed along walls where the vaults drained.

My second question was on the light inside the building which to my mind seemed limited from the deep skin corridor on one side and the small slit windows on the other. I also found the high sill heights of windows in classrooms limiting to the usable height for the children learning in the space. The opportunity to bring in light from the roof on the first floor also seemed like an underleveraged opportunity especially given that roof is not walkable. Samira largely agrees with me but also caveats that the sill heights were mandated by the school principal. She further cites cost challenges as limitations to being more expansive with light apertures and reminds me about the climate control dilemma which normally comes with big apertures for keeping spaces cool in hot environs. Owing to the larger than required emphasis on cost (especially given the big change of teams half way into the building), Samira’s balance between constraints and opportunities is evident albeit with the satisfaction of having won some critical battles along the way.

And to be nit-picky especially given Samira’s emphasis on well-crafted buildings, I bring up a column junction which sits awkwardly in a classroom on the first floor. Sharing my peeve on this, Samira submits that this was owing to a late change in brief where two classrooms were joined and one had to work with what was already built on site.

The Critic’s Chair

As is tradition I invite Samira to sit on the critic’s chair to look back and tell us what she thinks could have been done better. In a very honest way, Samira reflects that as designers one gets so close to an idea or a building that one is rarely able to take a step back to sometimes evaluate trade offs rationally. She takes us back to the limited natural light in classrooms which could have been improved simply by painting the classrooms white – something that eluded her owing to being engrossed as a designer with the materiality of brick and terracotta. Calling it an architect’s indulgence between form and function perhaps, Samira’s reflection is real and one that many of us face. Some challenges including a delayed term which meant that Samira could not see the building true to its full form and function remains a bit of disappointment for her. She also shares open feedback from the users that the waterproofing (despite early warnings) has not worked well (with 70% success rate) and requires regular maintenance leading to leaky joints. Samira does not shy away from this responsibility saying that buildings need to be built more robustly from our end. If cars don’t leak and Elon Musk can send people to Mars she says.

In summary for me, this chat with Samira has been more than insightful. I remain impressed with how she has overcome challenges on this project to stay firm on her sensitive and intuitive response translating it into a system framework of building design. The result is an evolving architectural dance of playful form for school children to enjoy in their space of learning.

***