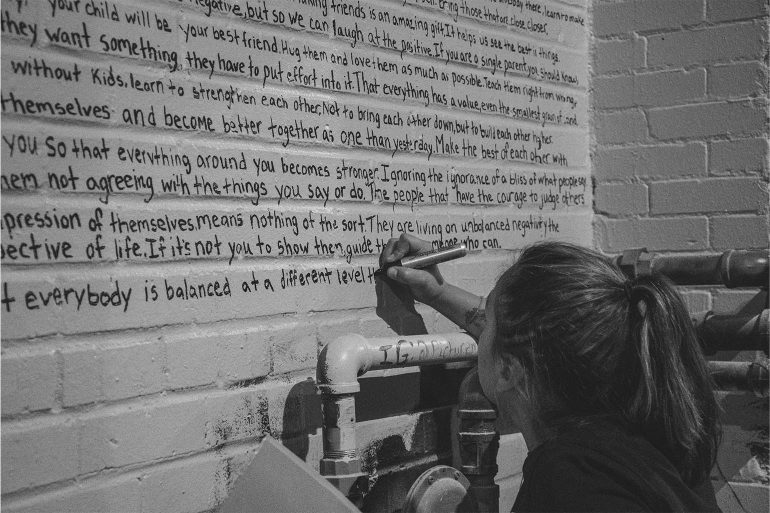

Walking into a classroom strewn with examples of design students practising lettering on large sheets of white paper, a few words leapt out at me – oblong, nostrils, demonic, universe, and – above all – author.

But more importantly, it was key to making the students realise that writing wasn’t sitting in a separate room, cloistered and suffocating, a task to be done that had no link with their other pursuits as first-year design students.

Intrigued by the choices, I constructed a writing prompt and chalked it up on the board. Soon, heads were bent over writing notebooks, as the kids attempted to make sense of the statement (Invented in a moment of improvisation, this has stayed with me, acting as a kind of guiding principle for future writing classes, allowing students to think about ideas of shape, universe-building, moral imperatives and authorial presence in ways I could not have then imagined!) — “In an oblong universe, the author has demonic nostrils” — plucked out of thin air, constructed with materials that they themselves had (unwittingly) offered me.

And that, in a nutshell, is what teaching design students writing is about, at least, for me. Part of life. No more, no less than a way of looking at the world through the medium of words.

As a demonstration that literally anything could become a starting point for writing, it was vivid. But more importantly, it was key to making the students realise that writing wasn’t sitting in a separate room, cloistered and suffocating, a task to be done that had no link with their other pursuits as first-year design students. Rather, it was part of a seamless continuum, the glue between one aspect of design learning and another – as material as clay, paper, paint, wood. As dimensional as their experiments in 3D object modelling. As kinetic as their first attempts at animation.

And that, in a nutshell, is what teaching design students writing is about, at least, for me. Part of life. No more, no less than a way of looking at the world through the medium of words.

That good writing can be as simple, as clear, as direct as the words you know – suddenly seems like a revelation.

For a full-time author like me – I quit advertising at the age of 28 in order to write my books – writing is central to my existence. I have to remind myself that is not true for those I teach! Over the years I have taken creative writing workshops for diverse audiences and age-groups, including intensive modules for those keen on writing as a career. I have worked with film and media students, with architecture students, and yes, with students of literature. What stays constant is understanding craft, voice, style. What varies is approach.

With design students what I offer is a great surprise – writing can be pleasurable! Without fear of words; without (even) a literary bent of mind. That good writing can be as simple, as clear, as direct as the words you know – suddenly seems like a revelation.

There is also a surprising sluggishness about coming up with things to write about.

A lot of my initial work with every new batch is discovering what their existing skills are. Having completed 12 years of schooling, there is always a certain standard of writing competency. Equally (and more depressingly) there is a standardization. A flattening out of personal quirks. A homogeneity of approach. A tonal correctness, verging on the bland, that makes me wonder what kind of strait-jacketing has already stiffened limber young minds. There is also a surprising sluggishness about coming up with things to write about. This is the fallout of invariably being given a “topic” for English composition. I’ve banished that word from my classes, preferring any substitute that will erase the tiredness of writing on a topic, with the mechanical correctness of a metronome.

My attempt, however, is not only to undo so many of the habits of regimented writing. My attempt is to introduce the revolutionary notion that writing isn’t a passive act. Instead, it is – it can be – as concrete, engaged and demanding as any specialised physical activity in the real world. Even when prompted to create analogies with things students love doing, like biking, deep-sea diving, or running, their expressions remain in the realm of the abstract. So writing is “as mysterious and deep as the depths of the ocean…” rather than filled with the beautiful specificities of the scuba-diver’s gear, the granularity of the names of aquatic creatures, the spectrum of identifiable colours in the coral reefs – each fact making the feeling what it is.

This may often mean redirecting them towards the original meaning of words they think they know. To investigate everything and return to the source; to be endlessly absorbent; and yes, to pull into writing class all that the other subjects have to offer.

This rift between fact and feeling, the imagined and the actual, the abstract and the concrete, the airy and the grounded is what I attempt to repair. The idea must be actualised, through observation, through experience, through attention. I attempt to lead them gently away from the grand gestures, the noble sentiments and hifalutin phrases (that no doubt won top marks in essay competitions!) and focus instead on the smallest things. To build from the ground up, one step at a time. This may often mean redirecting them towards the original meaning of words they think they know. To investigate everything and return to the source; to be endlessly absorbent; and yes, to pull into writing class all that the other subjects have to offer. To use their core interests as fuel for their writing; to use the tools, the techniques, the discipline and the exercises offered in class to develop writing as yet another means of visualizing their thoughts.

In the very first class I took, a young spark had piped up and asked, “Ma’am, will we learn fancy writing?” I laughed out loud, and asked him what he meant by “fancy writing” – which turned out to be exactly what I dreaded as much as the students. Could I help them see writing as I did – not as embellishment, but as essential? Not only a crucial means of thinking about the world but also – at a more artisanal level – a way of making objects that would exist, and be useful, in the world. Think of writing as a chair, I sometimes say, in order to pull them back from the empyrean heights. What kind of chair is it? An easy chair? A rocking chair? What kind of wood? What kind of polish? Is there a cushion? What kind of cushion? And so on and so forth…. By encouraging them to create each piece of writing from the centre of their selves, with care, precision and creativity, I hope they will no longer insist on false separations between image and word, design and writing, science and art.

***

Sampurna Chattarji is the author of twenty books, which include three novels; a short-story collection about Mumbai/Bombay, Dirty Love (Penguin, 2013); a collaboration between poets and artists, Over and Underground in Mumbai and Paris (Westland-Context, 2018); and a sci-poetry collection, Space Gulliver: Chronicles of an Alien (HarperCollins, 2020). Sampurna has been teaching writing to BDes students at IDC, IIT Bombay since 2018.