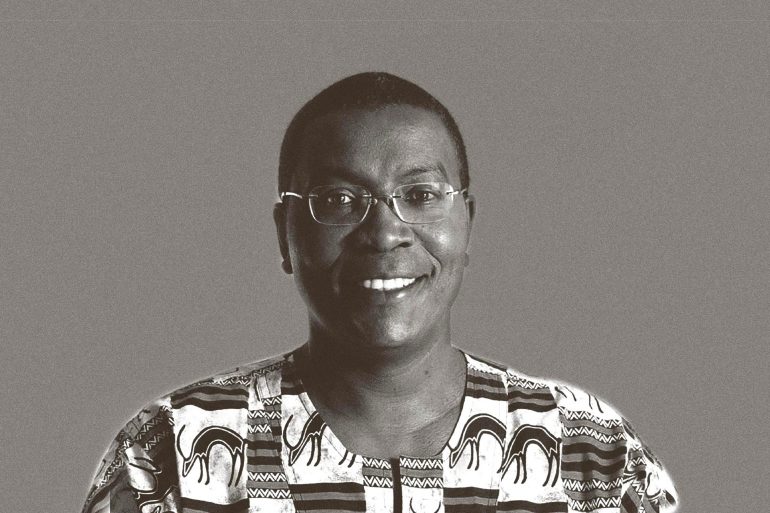

“My name, Mugendi, means traveler – which has been prophetic if I reflect on my life thus far,” replied Dr. Mugendi M’Rithaa, in an interview with John Thackara. Dr. M’Rithaa’s travels have taken him from Kenya to USA, India, Botswana and South Africa, where he has either studied or taught. He currently heads Postgraduate Studies in Design at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT) in Cape Town. Since 2013, he is also President-Elect of ICSID (International Council of Societies of Industrial Design), a not-for-profit organisation that supports the international industrial design community.

When referring to the African continent, Dr. Mugendi M’Rithaa prefers ‘majority world’ as opposed to oft-used labels such as ‘developing’, ‘third world’, or ‘the global south’. Statistically, these places do form the majority of humanity in the world today, thus addressing them with diminutive or marginalised terms seems inaccurate. An active proponent of Universal and Participatory Design, Dr. M’Rithaa’s primary agenda is design-aided development of the African continent. Interestingly, one of the milestones in his career, that cemented his interest in socially responsible design, was his time studying Industrial Design at IIT Mumbai for two years. His respect and admiration for India’s culture and education system runs deep, and we were curious to learn about the Kenyan-born designer’s journey to India and beyond.

Although Dr. M’Rithaa was born in Chogoria, a small town in the foothills of Mt. Kenya, he spent a few of his early years in the USA. “As a young lad in the USA, I watched the live moon landing – this event left an indelible impression on my mind and demonstrated the power of innovation and technology when rallied to solve real life challenges.”

Back in Kenya, while studying at Lenana High School, M’Rithaa had the opportunity to learn about woodwork, metalwork and fine art. He credits his fine art teacher, Ms. Themina Kaderbhai, for guiding him towards design. “I subsequently pursued undergraduate studies in design at the University of Nairobi where a number of lecturers laid the foundation for my life-long passion in design.”

After completing his undergraduate studies, M’Rithaa became “aware of the challenges and opportunities for design intervention in a resource-constrained environment.” He applied for and was awarded a Commonwealth Scholarship, which brought him to IDC (Industrial Design Center) at IIT. What drew him to India was “a perfect mix of base-of-the-pyramid socio-economic and socio-technical challenges that both majority world contexts as well as industrially developed contexts could interrogate.”

He adds, “I was cognizant of India’s leadership in the majority world, and thus resolved to study there so as to gain relevant and contextual knowledge that I could impart upon my return to Kenya. In Mumbai (as I later confirmed), I could be exposed to so-called ‘first-world’ and ‘third-world’ realities all within close proximity of each other. In hindsight, this was an inspired decision some two decades ago.”

This was M’Rithaa’s very first visit to India, and in the days before the Internet he undoubtedly must have had very little exposure to Indian culture. The first question that came to mind, was culture shock. “My arrival in India was a great revelation and reality check! Prior to my arrival, I had read about India and watched news bulletins with references to the sub-continent, yet nothing prepared me for the diversity, complexity and humanity that I was immersed into. Previous exposure had focused predominantly on India’s social, geographical and agricultural dynamics but paid scant attention to the geopolitical, economic, cultural, environmental and technological assets of the country. Additionally, news about India had played on traditional stereotypes predominantly in a decidedly negative light.”

Two years later, after completing his studies, M’Rithaa returned to Kenya, where he had been offered a job as a lecturer at the University of Nairobi. “My education at IIT, and the exposure from being immersed in India for two years was the best preparation I could have received before moving back to Kenya.” His new job gave him, “an opportunity to procure many excellent (and affordable) academic textbooks that formed the basis of my Industrial Design and Interior Design course material. I have since taught Industrial Design-related subjects at the University of Botswana in Gaborone, and for the last time at CPUT.”

As an educator in a majority world context, M’Rithaa takes the responsibility of supporting and nurturing younger designers very seriously. Not unlike India, one finds similar challenges to the development of design as a legitimate profession in Africa. Speaking of developing countries, he finds the lack of strong professional bodies that can support creative professions to be a serious limitation, compounded by the absence of “homegrown design strategies or policies, [which has] led to weak (or ineffective) protection of designers from exploitation as well as poor recognition and appreciation for their services.”

Global dialogue about design and inclusiveness tends to be lopsided – voices from developing countries are few and far between. There is also a tendency to ape Western ideologies, as a result of the lack of local design strategies. However, those ideologies often fail to acknowledge the complexity of living in India, or Kenya. A continent as vast as Africa is often viewed as a homogenous mass, a stereotype that irks M’Rithaa to no end. “There are assumptions that Africa lacks its own creative expressions and should thus be expected to blindly copy designerly trends emanating from distant and exotic places.”

For his part, through ICSID and other organisations, M’Rithaa is associated with a number of international networks focusing on design within majority world contexts. Comparing how design has changed through time, he says, “My observations over the last three decades have led me to believe that design has become more humanised and democratised.” M’Rithaa goes on to describe how it has become integrated with subjects as sustainable production and consumption, renewable energy and climate change. “The growth amongst designers in such poly-disciplinary areas as Universal Design and User Experience Design has blurred the boundaries of traditional design discourse with a clear trajectory towards transdisciplinarity. Designerly dialogue and facilitation now include a host of non-design actors in the quest to be more patently inclusive and potentially transformative.”

As designers, how can Indians, South Africans and Kenyans alike, shake off some of the misconceptions and stand on an equal footing with industrially developed counterparts? M’Rithaa emphasises that the onus is on designers living and working in such places to take the lead. “I believe that the world has never been more interconnected, yet open to novelty. It is incumbent on us as designers practicing in such contexts to articulate unique and authentic creative expressions from our own spheres of operation so as to inspire confidence locally and show leadership globally. An informed blend of advocacy and activism can certainly help to advance a more nuanced understanding of the evolving and expanded view of design from diverse contexts.”

Going back to the subject of India, M’Rithaa adds, “To my knowledge, India has a long and proud tradition that needs to be leveraged. India is renowned for its leadership in technology, ICT and the sciences. Indian classical music and Bollywood have massive global footprints too. In my view, the confidence that these sectors have shown needs to inspire a renewed vision of creative leadership – and to achieve this, designers must take a leadership role…”