Those Who Design series holds a critical lens to the contemporary architecture and design of our country. In the first conversation of the series, Professor Christopher Benninger, architect of the upcoming Azim Premji University in Bangalore, explains us the principles of designing at a large scale in India.

The Azim Premji University is a campus complex in Bangalore spread over 36 hectares of land and currently under construction. Designed by Pune-based firm CCBA, led by Professor Christopher Benninger, the project represents the necessities and challenges of designing a development of this scale in India. True to any urban exercise, the master plan has evolved over eight years of iterations from a structured comprehensive plan into an organic and incremental pattern language.

The campus includes 3,50,000 sqm. of built spaces composed of student and employee residences, dining facilities, sports and recreation facilities, classrooms, lecture halls, laboratories, conference rooms, faculty study rooms, an auditorium, art studios, music rooms, an amphitheatre, a library, essential utilities and a welcome centre. The site is somewhat limited by an existing temple and an erstwhile right of way that traverses across the site.

In this first conversation in the series Those Who Design we discuss with Professor Christopher Benninger the impact of education, institutions, and social impact of planning disciplines when we not just Make in India, but Design in India.

Those Who Design | Ep 1 — Conversation with Professor Christopher Benninger | Hosted by Anubhav Gupta

Designing for India

Professor Benninger’s endeavour has been to create positive social and environmental impact through design. He is however sceptical when architecture and design tend to get caught up in style to become collectors’ pieces. Adding to it, he believes that Western thinking on design particularly from the US/UK may not always be relevant to India. His scepticism is understandable given his choice of living and practicing in India despite his Western roots. He charmingly adds that people sitting in the West should not casually opine about Design in India without understanding her issues and working here.

His preference for exposed concrete, clean built form and articulation of building skin is reminiscent of other Western architects like Kahn and Corbusier who extensively built in India before him. While Benninger cares deeply about the unique ecosystem available in India, I was left wanting for a deeper conversation on how best this has been leveraged in his work over the years.

As a student of Kevin Lynch, he believes that planning in India has inherited strict hierarchical and divisive geometries from the romanticised era of the ‘Garden City’ — a method of urban planning in the late 1800s in which self-contained communities are surrounded by “greenbelts”. This ideology may have reflected in the planning of cantonments with distinct divisions for power, class and rank.

India has its own ecosystem with artisans, craftsmen, traditions, techniques etc, which enable designers to uniquely solve for India’s problems. Design in India is therefore a relevant conversation that needs to be had on multiple levels. Professor Benninger’s eye for detail and materiality is evident from his practice. His preference for exposed concrete, clean built form and articulation of building skin is reminiscent of other Western architects like Kahn and Corbusier who extensively built in India before him. While Benninger cares deeply about the unique ecosystem available in India, I was left wanting for a deeper conversation on how best this has been leveraged in his work over the years.

Building the Azim Premji University

For the Azim Premji University, it was clear that CCBA’s selection from a whole host of other contenders was sealed owing to a clear value match between the client and architect. While we did not get a ringside view of the conversations between the client and the architect during the master planning process, we were able to gauge how these values were in fact translated into the realised project.

In his own words, Benninger and his team at CCBA conceived the campus as a little town, which should be a framework of opportunities enabled by breaking down any divisions typically seen in urban planning or designing large master plans in India. The master plan is organised as a central pedestrian based civic structure that connects most parts of the campus. Benninger was clear that he wanted a pedestrian friendly campus, which is demonstrated from the fact that all/most motor traffic runs along the periphery of the site.

In his response to Bangalore’s water challenges, Benninger has integrated waterbodies to best harvest the resource within the site.

From an urban geometry perspective, while there’s surely an attempt to mix things up sans an intended hierarchy or division, it is not always clear what or how the separations (where they occur) indicate. The triangular teaching or faculty quads with key common buildings within them seem vibrant for its mixed use. However, may present other challenges in terms of noise and logistics when in use between teaching and other functions. Faculty residences and a school curiously find themselves slightly off the beaten track with weaker links and separate zoning from the main spine.

In his response to Bangalore’s water challenges, Benninger has integrated waterbodies to best harvest the resource within the site. The waterbody lined central spine leads to the raised rear of a giant Roman style open-air theatre pivoted off a large water reservoir which also forms the backdrop of the stage. The pedestrian spine works its way around the OAT and dramatically across the reservoir to lead to a court lined with two unusually tall student housing blocks facing each other and connected by a shorter dining facility block on the far end. Given the open vista of the views available on the site, it was interesting to note that either due to specific intent or for certain constraints, the tall student blocks were organised to face each other rather than open outwards for views across the site. While from a circulation perspective, Prof. Benninger has managed to keep the motorcar at the periphery, it is possible that given the site area of the campus, proportions and use, he may need to augment this circulation strategy, access and parking requirements as it grows over time.

Architecturally, Benninger is truly at his best in his use of clean forms which are beautifully articulated with exposed concrete and the use of a variety of double skin façades across all buildings. His command on materiality and architecture is masterful and his pursuit to create a transformative impact using design is evident. In doing so he manages to not only to politely assert his style but does so in a way that architectural design is used to contextually transform the environment and yet make his buildings collector’s pieces for posterity a timelessness of its own nature

He laments on the tall buildings, potential parking issues, evolving constraints that have tempered ideal masterplans and more greening of the site which he hopes will get better over time.

Every project, especially of this scale, comes with its set of challenges, which impact the design at various stages. While the final outcome may not be perfect, it is fairly optimized to a high degree in the face of practical trade-offs especially when there is a clear value match between the client and the architect. Now that the campus is coming alive after 8 years of hard work, Professor is stepping into a critic’s shoes and considering what could have been better.

He laments on the tall buildings, potential parking issues, evolving constraints that have tempered ideal masterplans and more greening of the site which he hopes will get better over time.

I am sure that Benninger is as eagerly anticipating to see the campus put to its use and to validate his thinking from a user’s standpoint particularly in his endeavour to break divisions, encourage equitable vibrancy, solve for environmental concerns and create a meaningful social impact via this little town of opportunities. While that jury is currently out, it is important is to keep this conversation alive; to learn and constantly strive to do better and make a transformative leap using Design and Design Thinking in the Indian context to solve real problems.

***

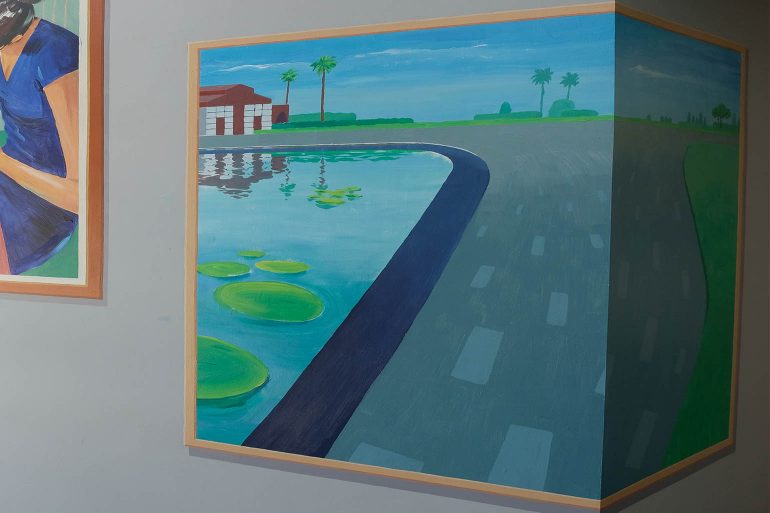

Feature image courtesy: Studio Vikhroli where this was painted by artist and illustrator Sameer Kulavoor.