Monika Correa’s love for all things woven would be evident even if she hadn’t made it her chosen method of practice as an artist. Whilst in her late teens a chance remark by a friend that the sari seemed to be designed for her made her take to it and, decades later, Correa draped elegantly in her enviable range of largely monochromatic saris seemed to represent all the weaving traditions in India. It’s been 55 years since she set up her loom and started her weaving practice, one that she pursued after seeing Rya rugs on a trip to Finland with her husband, the late architect Charles Correa. Minimalist yet deeply evocative, her tapestries employ her own innovative techniques to render stillness and movement.

We go through several images, where variations of a rigid start segue into areas without the reed. Using this method she manages to manipulate the image and obtain the mood. The abstraction allows for play with form, images that can break the 2D plane, disrupting the surface organically, bringing in texture and movement that make these still images come alive. There is a meditative quality to some of the pieces, meanderings that throw out of focus a certainty, keeping the viewer discovering anew. Though often spartan, colour, design and texture bring a richness, however pared-down the form.

We start our conversation in a book-lined room next to the living room where her loom has occupied centrestage for so many decades. She pulls out a catalogue of a show at the Pucker Gallery in Boston in 2014. I pull her back to the beginning.

How did you start your journey in weaving?

Charles was invited to MIT, in 1962, and we travelled via Finland. In Helsinki, textile designer friends took us to see the weaving there, and I loved what I saw. The rugs were abstract—thick wool and deep colours. There were no little flowers or patterns drawn and, because I can’t draw, I was fascinated by this, and I thought this is what I want to do.

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, Charles was teaching, and I had time on my hands. Charles’s teacher was the artist Professor Gyorgy Kepes, who led me to Marianne Strengell, a Finnish-American, who was head of the Cranbrook Academy of Art’s textile programme. She was very good to me and taught me the fundamentals of weaving. When I was returning to India, she gave me a design of a loom and mentioned her former student who lived in Bombay, Nelly Sethna. [Back in India in 1963, Correa had the loom built.] Sethna sent a younger weaver who knew just the beginnings of weaving, and I too knew just the beginnings, and this worked out well… One was willing to experiment.

You are largely self-taught in what came later, but the basics you learnt at…

At the Weavers Service Centre [Mumbai]. I did a three-month course, just half days. It was wonderful. The director of the Centre, [Sudhir] Sojwal, came over for dinner to meet a Danish designer staying with us. He suggested I come over to the Opera House branch where I could learn.

That was very good. Because at that time the artist KG Subramanyan, who was in Baroda, had a three-month stint every year with the Weavers Service Centre in Mumbai, which Pupul Jayakar had arranged. He was a great influence on me because, using wool, he made what he called fibre sculptures and that fascinated me, I had never seen anything like that. And he used a wool from Gujarat which had a nice texture.

Jyotindra Jain talks about the Weavers Service Centres and how they should be centres for revival now. Were they open to all?

No. Sojwal was very nice to me. But they were also doing it for international goodwill. While I was there, there were two Kenyan girls too. But I was very lucky, as I told you, that there was KG Subramanyam and Jack Lenor Larsen, the guru of American textiles. He was looking at everything. Lenor visited Kanchipuram, where Charles and I had been. I had given a sari to be woven according to my design and colours. Lenor saw that sari and asked the weaver who would wear a sari like that, and they said there is someone in Bombay, Monika Correa, who has ordered this. He came back and told Sojwal: give her any colours and whatever she wants. So I think I was lucky I was there at a time like that. Also, I was with a lot of designers—Abhijit Barua, Shona Ray, Riten Mozumdar.

Then it so happened that Pilloo Pochkhanawala was holding the first Bombay Arts Festival and, as a great gesture, she said, “Monika, would you do a tapestry?” I was pleased no end!

This was a year later, and you had started weaving pieces?

This was about ’65. I went to Sojwal who let me take whatever wool I wanted which I could replace later. I did the piece “Original Sin” and another I put up two pieces at the Bombay Arts Festival. Nissim Ezekiel wrote about the show: “wonderful weaveby Monika Correa and KG Subramanyam”. That spurred me on as Nissim was very highly thought of.

Why have you always worked on tapestries and not rugs? Was this right from the start?

When I just began weaving I started working on dhurries, the simplest and easiest start to weaving. But, having taken so much trouble, I could not bear the idea of anyone walking on them! When you put them on the wall, you look at them differently.

I use a twill weave on the diagonal for all my weaving. If it had been a straight weave I had gone in for, there would have been a lot of limitations. A twill weave gives another dimension, a kind of tension, a kind of activity to the otherwise docile textile. Also, for a weaver to work on a diagonal is unlike an artist—it cannot be a spontaneous single gesture. We work horizontally and a diagonal in any image has to be built up.

My knowledge of weaving was not very intense so I was always experimenting and I would learn along the way. As I worked on the vertical and horizontal looms I wanted to bring the fluidity of the warp seen in the vertical loom to the rigidity of the horizontal. I realised I could do this by removing the reed on the horizontal loom, as the reed keeps all the threads intact.

So it was the creative process that led you to innovation…

At the Weavers Service Centre, they said, it’s impossible, Mrs Correa, you can’t do it! The manufacturer, too, said you can’t do anything. So I got hold of a carpenter and with an electric saw we chopped off the top of the reed which has these iron filings stuck with tar and took the wooden rack and screwed it on. This allowed me to unscrew it and take it out as and when I wanted.

What was it like being around Charles’ work?

I have been very influenced by Charles, his many friends like KG Subramanyan, Riten Mozumdar, Philip Johnson and Bucky Fuller. Charles’ architectural drawings were a huge influence. The geometry in my work came from being around those. His teacher, Gyorgy Kepes, was a painter, whose sense of colour had a deep influence on us. In “Homage to Kepes”, I use the pink and orange he would use in his own work, colours he would say bleed into each other. It’s also a work where there’s a thick pile surround to a central rectangle where the warp meanders. It ties many early influences and later experimentation together.

**

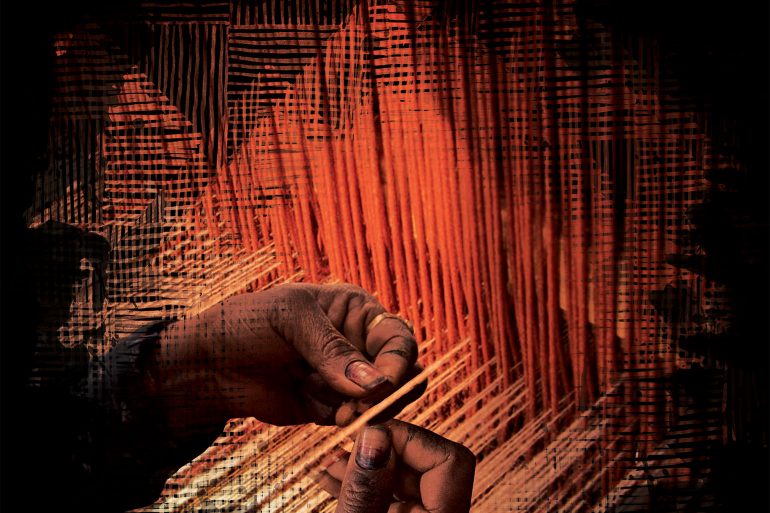

A longer, detailed version of this interview was published at the Indian Quarterly magazine. Feature image from Bunkar, The Last of Varanasi Weavers by Narrative Pictures.