In 1922, Pherozesha Sidhwa, a would-be lawyer, was pushed on a different path. Propelled by the Swadeshi movement, he was encouraged to take up industry, which in turn led him to tile making, a field he had absolutely no footing in – and so began the Bharat Flooring Tile Company (BFT). Whereas naming a company ‘Bharat’ is nothing unusual today, back then it was a strongly patriotic gesture. And in the same manner as other companies that started around that time, the sole intent was to shake off India’s dependence on British-made goods by bringing manufacturing back home; accompanied by a sense of pride in creating products that were “Equal to the world’s best”, both in quality and durability. The first lot of BFT tiles produced were thrown into the sea when they were deemed to be of inferior quality. It was later discovered that while the tiles were perfect, the polishing was not.

“Bharat Tiles always remained small, it was always the baby of the family. There was a very small production, very quality-conscious. Which is why after a while, companies like Nitco went much further ahead because they were more about mass-production. Even today we still continue with the same tradition of being quality-conscious and very niche. Our production is not massive, it’s more about passion and enjoying making something beautiful. And providing employment to a lot of artisans – these guys who make the tiles for us. It’s a dying art which is being kept alive, and it’s good fun at the same time,” explains Firdaus Variava, Vice Chairman and grandson of Pherozesha Sidhwa.

[Above, Left: Old identity of Bharat Tiles; Right: New identity of Bharat Tiles done by Idea Spice]

The Bharat Floorings & Tiles office stands where it always has, on Mumbai Samachar Marg in Fort, Mumbai. It is intrinsically linked to one’s mental image of ‘Old Bombay’, even for those who may never have heard of the company itself. Walk through Mumbai Central Station, David Sassoon Library, or any of the countless heritage structures strewn across the city and one can guarantee you’ve walked on a floor paved with ornate Bharat Tiles. Recently however, you’re also just as likely to see them in trendy cafés, restaurants and some of the finest homes. Owned by three generations of the Sidhwa family, and currently managed by Firdaus Variava and his mother Delnavaz Variava, Bharat Floorings & Tiles, and specifically their handmade collections of patterned tiles are enjoying a revival of sorts. But this wasn’t always the case.

In conversation with Firdaus, we came to learn that the company has had its share of setbacks over the years. For instance, at the beginning of World War II, when the British impounded their entire stock of cement for war purposes, the factory came to a halt without its most essential raw material. “[It was] with the help of two Jewish gentlemen who were stranded and unable to go back to Germany, that my grandfather started a second company, manufacturing grinding wheels and abrasives.” Today this company is known as Grindwell Norton.

While Art Deco was transforming Mumbai’s coastline in the 1920s and 30s, it also signalled the end of anything ornate, in favour of a geometric, machine-like aesthetic. Bharat Tiles’ floral patterns were out of fashion, and terrazzo (a tile made of chips embedded in coloured cement) were all the rage. Even though they began manufacturing terrazzo to meet new demands, because of the Sidhwas’ emphasis on impeccably crafted handmade tiles, the company was continuously overshot by cheaper, faster, mass-produced counterparts. Whereas by 1960 it held a virtual monopoly of the tile business, by the 80s the company was on the brink of shutting down; and revenue from renting warehouses sustained the manufacturing side for a few years. By this time, the signature heritage tiles had fallen out of popularity, and were no longer being produced.

In 1999, for a heritage exhibition at the now-famous Kala Ghoda Festival,“someone asked my mother if she could make some of the old tiles we used to make in 1922. My mom pulled out the old moulds and she made some of the old tiles.” People were so impressed by the tiles, that they began to receive orders from restoration architects, for projects such as Bhau Daji Lad Museum and the BMC headquarters. However, the company was still producing the same old designs alongside mass-produced tiles. Those tiles were being used for factory floors and public spaces with heavy traffic, which was no place for the painstakingly produced heritage tiles. This was also an area where Bharat Floorings could not keep up with the competition, thus it was imperative to create a new image and focus on a completely different clientele – to move from being functional flooring to be appreciated for their artisanal value.

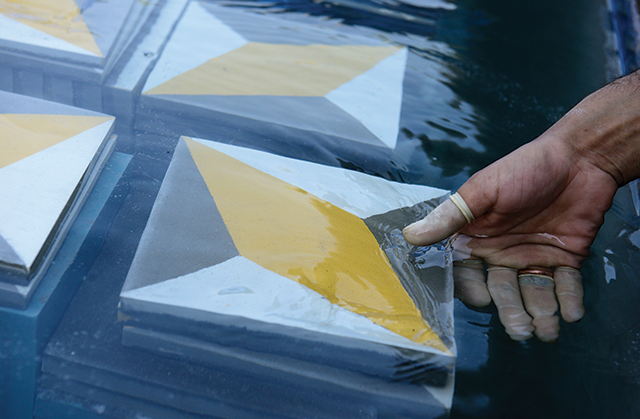

Finding and training skilled craftsmen is a challenge in itself. “A lot of the pressmen have been with us for a while but some are new. For us to ramp up production, we had to train new people. This is also more like the unorganised sector, they [workers] might suddenly decide to go home, and they’re gone. It’s not really easy to find people. The one thing we do is start off with the lowest category, which is the most unskilled laborers. A guy will come in to the factory and help the pressmen, or bring cement to them. After a few months he’ll move on to making plain tiles. It’s just putting colour inside a mould, no divider, and pressing it – Even this is quite hard and there are a number of things you can screw up – And then they’ll go on to making heritage tiles. That whole process takes about 6 months, but by then you’ve got an unskilled guy who’s learned a new skill he can use.”

As the business has progressed, bespoke and designer tiles have taken over, and the company is less and less involved in public sector projects such as railway stations. “Basically the same people who can make a heritage tile are being used to make a very cheap tile. So we don’t want to do it at all, we’re thinking of giving up that business altogether.”

Firdaus’s arrival was a pivotal moment for the company. Unlike a typical descendant taking over a family business, it hadn’t been a natural choice for him. At the suggestion of his mother, Firdaus took a break from corporate life to give it a shot. Eight years later, he is clearly the driving force behind the company and its new direction. While they used to receive a number of orders for custom designs, Firdaus saw the potential in creating their own designs using the techniques they had already perfected. “I started meeting younger designers like Tejal Mathur and Ayaz Basrai, and they were adapting the heritage designs with their own colour schemes. We started to make different colours, more pastel, contemporary. That was the next phase that began, and it’s only been about 4-5 years that we’ve been doing it in a big way. People were coming to us with very specific ideas, and they started coming to us with designs.” One of the issues Bharat Floorings faced was that designers would not let them reproduce the designs.

In 2013, Bharat Tiles produced a collection designed by Le Mill, a Mumbai boutique. “Last year, the collaboration with Le Mill was working out and showing some results. So I decided to talk to some of the designers who worked with us and ask them to proactively design new ranges for us.” This was followed by a complete re-branding by Idea Spice Designs and more collaborations with Alice Von Baum, Sian Pascale and The Busride, and eventually Sameer Kulavoor.

One would imagine that the price of handmade tiles that take 30 days to produce would be exorbitant, but we are told that they are priced only slightly higher than the machine-made alternative. “We also kept the prices intentionally low because we want people to afford it. The ones from the designers are the luxury range and there’s a slight price increase. The thing is, all these designers have contributed their work almost for free, so we wanted to make sure we sell the tiles so that they can be remunerated from the sales of tiles. We haven’t priced it exorbitantly, but kept it at a level at which people will buy it and we can give designers some royalties.”

From cement doorknobs to furniture and lamps, there’s nothing they won’t experiment with, so long as it’s made of cement. And Firdaus and his team are eager to work with more designers on new collections. At the moment their primary focus is expanding geographically, beyond Mumbai and Bangalore, as a way to maintain a steady stream of orders. They are also exploring ways to speed up their prototyping and manufacturing process, with the help of emerging technologies such as 3D printing. It’s encouraging to see a 90-year-old organisation eager to adapt and experiment, armed with confidence in the quality of its product. Looking at their beautiful new collections, it doesn’t seem like Bharat Floorings is going anywhere anytime soon.

**

A version of this article was published in Kyoorius 24.