Yasaman Esmaili grew up amidst transitioning political and religious climate of Iran, yet appreciating her country’s rich architecture. After graduating from the University of Tehran in 2008, Esmaili moved to the US, where she pursued masters in architecture and worked on her initial projects. For her first project, she was part of an international team to design the Gohar Khatoon Girls’ School in Afghanistan. She worked remotely on the project. Two projects in Niger followed—a housing project, and a mosque and library. These projects strengthened her ideology of understanding the community and local building culture.

Esmaili has set up her studio practice, Chahar, between Tehran and Boston. Chahar meaning ‘four’ in Farsi, is used in many architectural terms chaharsoo is the center of the bazaar, chaharbagh is garden with a quadrilateral form, just like in Northern India. Her current projects are based in Qeshm island, Iran, to save mangroves, build refuge pavilions for tourists, and build Persian jahaz or wooden boats using the disappearing weaving techniques to build boats. The mangroves and wooden boats are UNESCO registered heritage sites. Just a few days into the project, Ismaili flew into India to present at the Women in Design 2020+ conference, where she spoke to us at length about her work. Excerpts here:

The escalating political tensions between US and Iran has the entire world worried. Your newly started studio practice is based in both countries. Does the looming threat of war make you nervous as a young professional who is working hard to establish herself?

A friend of mine put it in a very good way. For the last 350 years, people have always lived in a state of emergency, ready for things that can happen. Not only Iran, many, many countries of what is called the South. We have grown up with this thing in us that anything can happen at any second. I think that’s the only way that I can respond at all because things has always been very politically conflicted since I was born. It’s not about not being nervous, necessarily, but that nervousness is part of you. You are not always questioning it, and it’s not so odd. It is just there.

A major threat made by the president of the USA is complete destruction of sites important to Iranian culture, which essentially means the built heritage and cultural sites. As an architect, help us understand the atrociousness of this threat.

When you talk about cultural heritage in Iran, you talk about sites that are about 4000 years old, or even older. They’re located in Iran, but they are world heritage, we all own them together. It’s history, and not about one country. I don’t know why he would think of doing something like that to those cultural sites. And there are civilians who are always around those cultural sites. And, yeah, Iran is this great, amazing country in terms of cultural heritage and history. I’m from Iran, I grew up there, I studied there. But that a statement would be wrong about any cultural history in any country; when you use the term ‘cultural’ and/or anything about people, threatening it is wrong.

Architectural heritage, local materials and cultural context have been an important part of your work. What do these aspects lend to a build structure that makes it meaningful?

It is the history. It’s the story in every building. When you arrive at a place to do something, it’s about being humble and learning that story first. There is that beauty, those moments of joy when you find out something about what was happening here before—a specific technique or a way of building things that meant something and is still working.

In many places, we have stopped using the local knowledge, what we had for thousands of years, and jumped to new ways and techniques that are not. Because we are missing last hundred or 50 years, we don’t know what to do, we are confused. That confusion shapes itself in nostalgia or we completely try to look like Western countries, because we don’t know what to do. If people had come up with ideas and built structures two or three generations ago, we could keep going the same way and wouldn’t talk about it as traditions that are not there anymore. It would they would have evolved and they would be contemporary.

You studied in Iran and then in the US. Did you feel there is a Western bias in architecture education in the US?

Definitely, and I don’t think it’s conscious. It’s just because it’s formed the way the institutions are formed. Even in our in the eastern countries we follow the Western countries, even though the way we had education was very different before. They have done more of what they call research within their own institutions, and we don’t have that. I experienced this a lot actually. And not only me, many, many other students studying architecture who want to do something about a topic in their country, and the professor would feel like there’s not enough resources for you to look into it. Even if you say, ‘I’m going to go and do field work’, they will want to see a published paper. So, there’s definitely that problem.

You’ve also worked with displaced communities in the US. It’s 2020, and we are anticipating more forced displacement. Can architecture help in addressing questions of space and identity in displaced communities?

I definitely think it can. I think we are all displaced, we are all always moving. It’s just that some of us are more fortunate, and displacement happens to us, maybe, with better choices, or it’s not as forceful. But I think what architecture can do is to acknowledge this to help the communities, especially children cherish the memories and identity they have left behind.

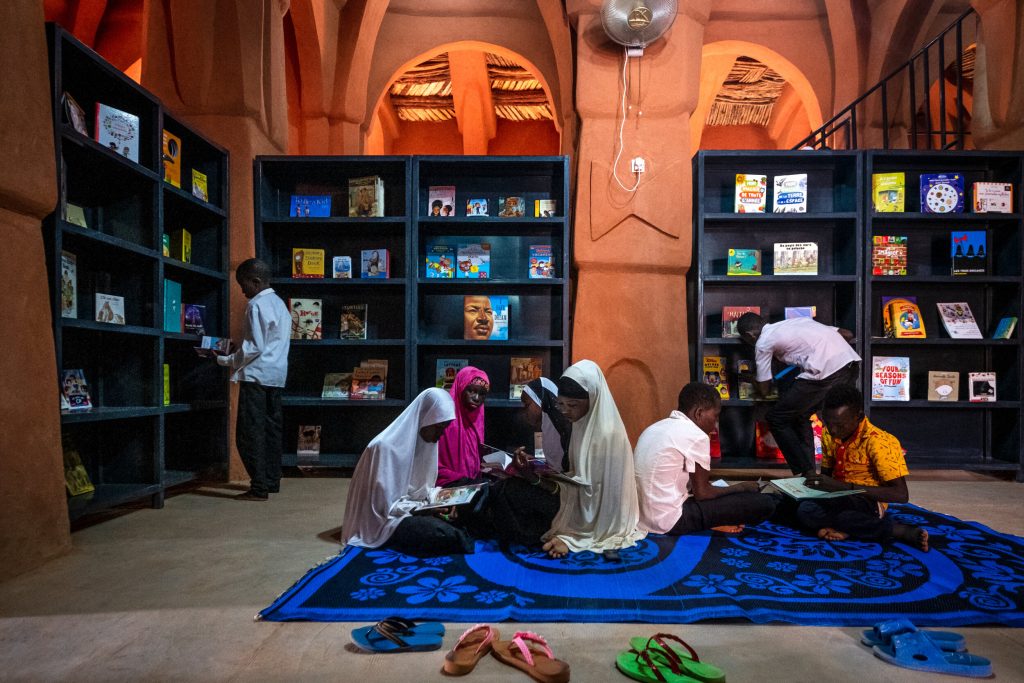

Project by Yasaman Esmaili, Rania Qawasma

How are women architects received in Iran?

When I go back to Iran, they respect me more. Even though I’m a woman, because now I have the ‘Western thing’. (Laughs.) It’s weird but it happens. In Iran people think that I now have exposure to places that they don’t. But yes, like many places, Iran has that problem, where you are looked at only as a woman. I really try not focus on anything that is about me being just a woman. It happens, but I just deal with it like any other problem, and come up with a solution, be flexible and understand what they’re asking for.

Though things are much better in the US even, women in Iran are fighting a lot harder to make things change, which I think is similar to India. I was a lot more involved in discussions about how we can take actions naturally, focusing on being women in action, but being aware of the fact that there are problems.

Studio chahar is working with the Gouran cooperative, a cooperative company consisting of 100+ households of the Gouran village, to develop a new typology for a the ocean liner, as a passenger ship that will be used for sustainable tourism

Where do you turn to for inspiration, or just to unwind and calm yourself?

It’s a big part of me to read Persian poetry. I write poems sometimes. And I grew up with it. It’s a culture, particularly in my family. When I talk to my dad, he would respond with a poem sometimes. I read Hafez a lot, and I read Rumi. There are these notions of focusing on the present, letting go of yourself and being more inward looking. These are very hard. It’s kind of meditation to me. It doesn’t necessarily influence my work, but it influences the way I think.

**

All images from Studio Chahar.