After India’s independence in 1947, the government adopted a pro-socialist model. However, in 1991, the tide changed. The year ushered in a new set of reforms which opened the Indian economy to the global market. Foreign and private investment increased and businesses from overseas came to India. This led to the rise of private sector jobs in urban areas, further leading to creation of the urban middle class.

Urbanisation marked a shift from joint families who lived in independent houses to nuclear families who lived in apartments. This changed the position of the kitchen—earlier a service core at the back of the house, it was now at the centre, just a step away from the dining room, the most public area in the house. At the same time, middle-class women started to pursue education, take up jobs, or become entrepreneurs. As both men and women started stepping out, dining habits began to change.

The financially empowered urban middle class aspired foreign products and wanted their homes to reflect an international lifestyle. Soon, ‘Lifestyle’ emerged as a category in print magazines, one of the most dominant and influential forms of media, especially from 1950s to early 2000s. They influenced purchase decisions and shaped consumer behaviour.

Print magazines defined the way of living and thinking

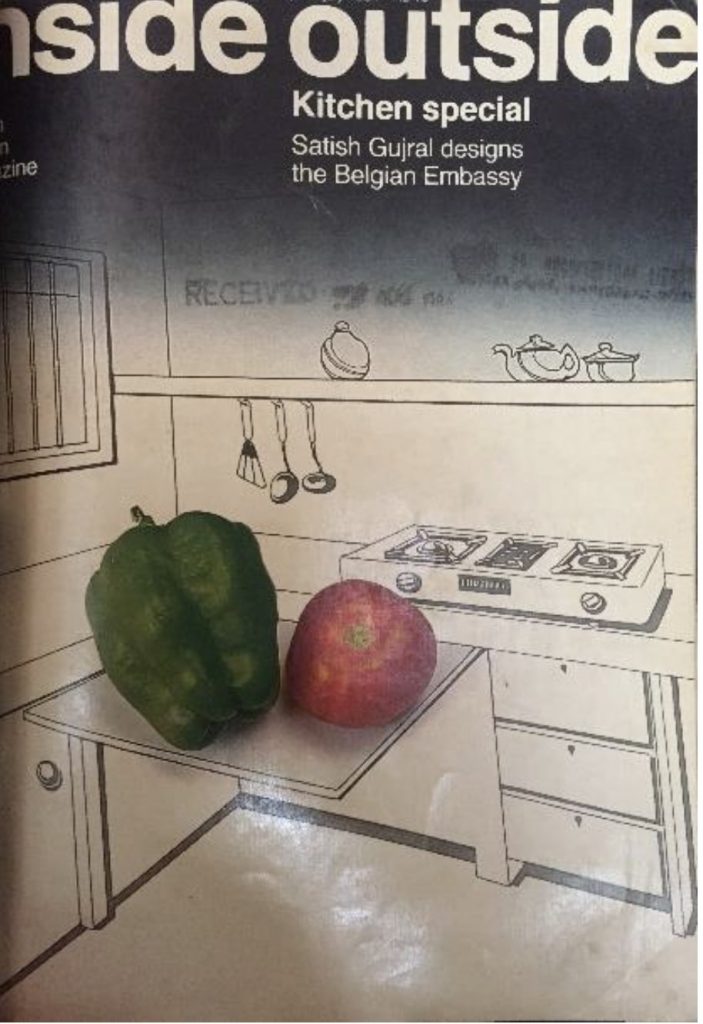

A widely read homegrown magazine, Inside Outside, was launched in 1978. It was the first interior design magazine that targeted non-design professionals. The issues of Inside Outside from 1980 to 2010 tell us the fascinating story of the evolution of the Indian kitchen.

Inside Outside was launched when our country was dealing with a severe financial crisis. The issues discussed subjects of national importance like rural health and the International Trade Fair 1979, along with architectural projects that ranged from economical housing to affluent interiors. But essentially, it saw itself as a mentor and guide in home-interior space.

Source: CEPT University Library (Ahmedabad)

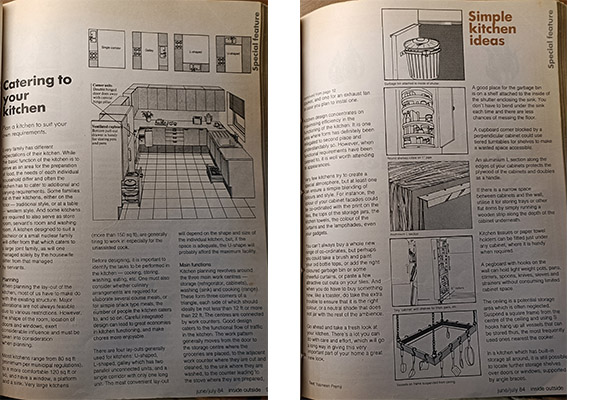

In the first six years, the magazine focused on living areas such as the drawing and dining room. But in the summer of 1984, a kitchen special issue was launched—first time for a national publication to bring a service area of the house under spotlight. A kitchen special issue meant that women formed a large part of the target readership, and were now seen as stakeholders in decisions related to the interiors of the kitchen.

Source: CEPT University Library (Ahmedabad)

Women as readers and decision-makers

The editor’s letter in the first kitchen special issue of Inside Outside addressed the busy housewife. Considering the kitchen as the metaphorical centre of the house, it was a space that needed to be functional, compact, requiring little maintenance, and performing the role of pantry and store. The letter said, “Today the domestic servant is fast becoming an extinct breed, vanishing, as are the spaces he ruled over, and the housewife is forced to step into the kitchen and take on the domestic chores herself.”

The focus of the issue was on efficiency and storage planning. An article titled, “Catering to Our Kitchen” discussed the unacceptability of men in the kitchen, a kitchen’s functional aspects and the hazards of a sitting kitchen. The issue also carried an expert section covering various aspects of ergonomics of kitchen design, by Dr GG Ray, a professor at the Industrial Design Centre of IIT Bombay. He discussed the appropriate height of the stove, platform, shelving, storage and material finishes that would best suit the human body.

Source: CEPT University Library (Ahmedabad)

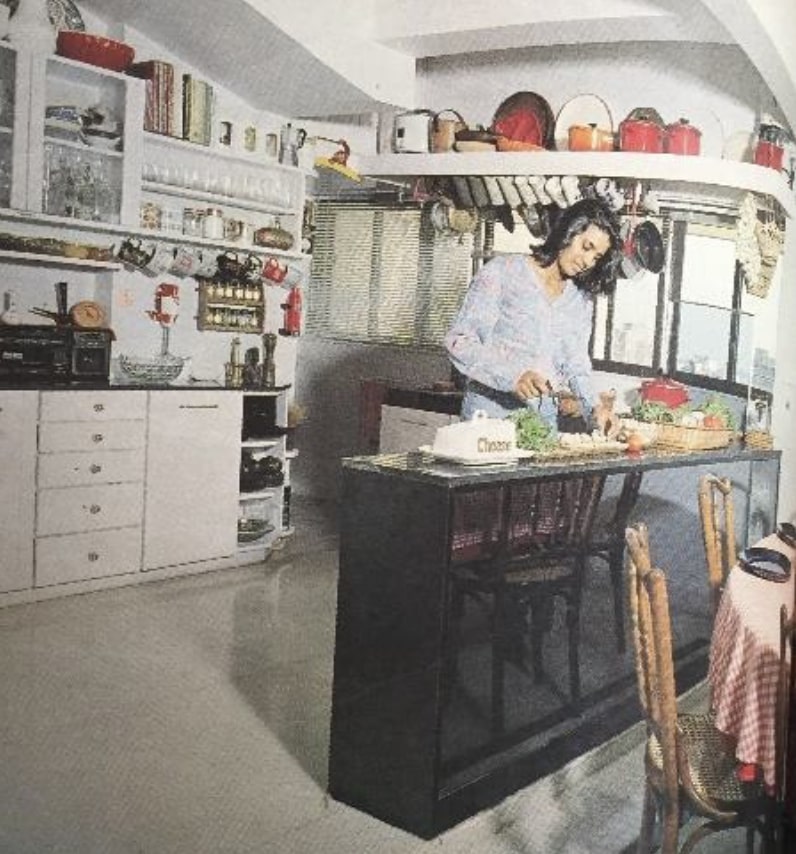

The features were written in a conversational tone, and the magazine saw itself as a friend-guide that sought to help the woman reader in building her perfect kitchen. The August 1992 issue of Inside Outside featured a project wherein the housewife was the coordinator of all activities, and a major decision-maker in doing the interiors along with the architect.

Source: CEPT University Library (Ahmedabad)

The kitchen and the women in advertisements

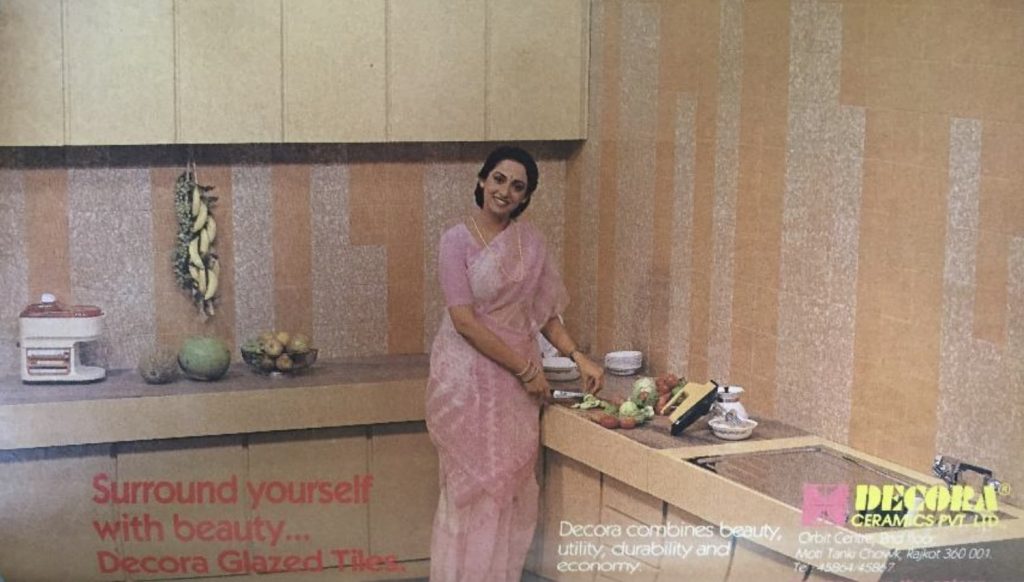

The kitchen also began to appear in product ads. After liberalization, several modular kitchen and kitchen hardware brands flooded the Indian market, and their ads began to dominate the pages of the magazine. The first advertisement featuring a kitchen was that of a tile brand Decora in the June 1988 issue of Inside Outside. The advert showed a happy housewife in an uncluttered kitchen.

Source: CEPT University Library (Ahmedabad)

The ads reflected conflicting ideas — some reinforcing that a woman’s place is in the kitchen, some showing the kitchen as a place where the family comes together, some showing the woman beyond domestic confines.

In the late 90s, the punch-line for the brand Antares Kitchens was, “With such an exquisite kitchen, husbands may see less and less of their wives.” The first kitchen special issue, almost a decade ago firmly kept men out of the kitchen, the adverts of late 90s had them donning aprons. In fact, an early-2000s ad of the furniture hardware brand, The House of Ebco shows the entire family in the kitchen, smiling, and in the kitchen.

Source: CEPT University Library (Ahmedabad)

Yet, the pace of progress has always been staggered. An early-2000s ad of hardware brand, Evershine Utility Systems’ tag line said, “A woman’s right place is in the kitchen… I am glad to agree”. However, the woman shown here is not the traditional sari-clad woman of the 80s adverts; she is dressed in western clothing, seemingly coherent with the times. In the mid and late 2000s, the ads of the Italian modular kitchen brand Aran Cucine showed a different idea of the woman—as a professional and a party-goer, with the tagline, “Look who’s cooking?”

Source: CEPT University Library (Ahmedabad)

Though the first kitchen special issue of Inside Outside focused on efficiency, aesthetics and visual appeal dominated the kitchens from the 2000s. As the Indian kitchen continues to evolve with new technology and brands, there lies much potential to understand the change in representation of kitchens in media, and the actual transformations in real life.

***

Deepika Srivastava is currently working at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad on a project focussed on empowering minority craft communities of India. A graduate of the MA History of Design programme run jointly by The Royal College of Art (RCA) and Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Bachelors in Interior Design programme of CEPT University, her creative practice revolves around telling stories about culture and design. She is also involved in starting a network to establish the discipline of Design History in South Asia.

*This article is based on research conducted by the author for her dissertation during her undergraduate studies at the Faculty of Design, CEPT University, under the guidance of Prof. Snehal Nagarsheth, then Associate Professor at Faculty of Design, CEPT University, and currently Dean of Architecture at Anant National University.